Last Spring, I took a trip to a sustainable community in North Carolina. The creator of “Turtle Island Preserve” inspired my Appalachian Trail thru-hike in 2015. And I wanted to meet the man who changed the course of my life.

Eustace Conway spent 17 years of his youth living in a tipi that he’d made himself. He lived in the Appalachian Mountains, capturing what he ate. And he, himself, hiked the Appalachian Trail southbound when it was a lot more rugged and inhospitable.

Elizabeth Gilbert wrote a book about Eustace. And in the description, she explains: “In 1977, at the age of seventeen, Conway left his family’s comfortable suburban home to move to the Appalachian Mountains. For more than two decades he has lived there, making fire with sticks, wearing skins from animals he has trapped, and trying to convince Americans to give up their materialistic lifestyles and return with him back to nature.” I devoured Eustace’s story once. And then I read it again and again. And five years after I learned about his existence, I knew I needed to meet him.

Meeting Eustace Conway

The first time I saw Eustace, he was wearing a grin more welcoming than any I’d ever seen. He wore his silver hair in loose braids that jostled with the dump truck he drove. He’s an introvert and he chooses his social gatherings more selectively as he grows older. But he has a lot of big ideas, and he’s determined to teach those who will listen.

The island’s inhabitants speak about the man with equal parts respect and worry. He works harder than anyone I’ve ever met. And at age 57, he seemed more alive than anyone I’d ever seen before.

I remember being taken aback by the way that Eustace communicates. The legend has spent his life in the blue ridge mountains, attempting to reconnect humanity with the environment. His eyes never darted to another place while engaged in conversation. And he always knew the perfect questions to ask to startle your sense of understanding.

A Lesson From Turtle Island Preserve

On one particular evening, we shared our thoughts next to an unlit fire pit as darkness descended. Eustace said that he suspected that the root of society’s problems relates to disconnection.

We spend entire seasons controlling the temperature of our homes, closing the windows to discomfort. We let our food spoil because when you can pluck it from the shelves of a grocery store, the supply seems endless. And perhaps the most disheartening truth is that we treat each other with the same impartiality. Why mend our relationships when we can swipe right on an app to find a replacement?

The Era of Disconnection

It seems as if we’re more connected than ever before because we live in the era of technology. I’ve spoken to friends from across the globe at no cost to myself. News travels at the speed of light, so it seems as if we’re involved with each other’s lives even when we’re not. And yet, we are the loneliest generation in history.

A 2018 survey conducted by Cigna showed that most adults (18+) are lonely. Only 53% of U.S. Citizens have meaningful social interactions on a daily basis. And the Millennial generation is one of the lonliest in history. Oddly, there’s a link between time spent on social media and feelings of isolation. So, as our “connection” with social media grows, so does our sense of loneliness; We strive to make connections while becoming more disconnected.

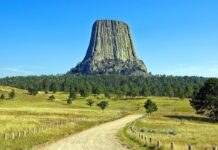

It doesn’t seem surprising to me, now, to see how a man who basically spent his life in remote Appalachia is more connected than anyone I’ve ever met. Eustace chose to construct his life in a conscious way. He created a 1000-acre sanctuary where there’s no cell phone service or electricity. The happiness that emerges from visitors in this place is palpable. And I don’t think it’s a coincidence that it exists in a bubble that’s removed from social media.

The Natural Mountain Connection

I think part of what draws me to the mountains is their ability to facilitate connection. You can’t escape the sun, hail or snow while you’re scaling a peak. So, you’re forced to co-exist with discomfort rather than hide from it. But alot of mountain ranges haven’t yet been intercepted by cellphone service, either. Even if you wanted to spend time posting photos on social media, you’re much less able to do so from a ridge.

Turtle Island and Eustace Conway exhibit this phenomena from the belly of Appalachia. Eustace is as much a part of Appalachia as the mountains, themselves. So, it only seems natural that he’d understand the nature of connection.

Perhaps I’ve been particularly attuned to the idea of disconnection because I, myself, am feeling disconnected. Every time I think about the presentation of a photo on social media, I’m reminded of the lens through which we see one another’s lives. We’re privy to a partial view. And I want to find a way to see the whole picture.

Finding Connection

If instant gratification is an addiction, will removing the stimuli change our relationship with the environment? And with each other?

How have successful communities been built in the past?

Do you feel that you can rely on your community when life gets tough?

Will finding the source of disconnection help to reverse the problem?

For More Inspiration: